Horror Analysis Act 2/ The Usage of Hair Motifs in Masaaki Nakayama's PTSD Radio

Part 2 of understanding how Religious and Spiritual Cultural Contexts are used in horror manga

[4] Chapter 2: Hair in a Religious Context

Subchapter 1: Hair in Relation to the Japanese Gods/

As outlined in the in troduction, Japan places a heavy emphasis on upholding traditions, most of which stem from their main religion, Shintoism. Shintoism shares many of its ethics with Buddhism, developing as a result of ‘Buddhist teachings being imported from China'. At its core, Shintoism is the belief and worship of a plethora of God's, known as ‘Kami’. These Kami do have a Social hierarchy, as is common in religions with more than one deity, but the extent of how many Kami exist in the human world is what sets Shintoism apart from other belief systems. The Kami can exist anywhere, living within ‘material objects, usually natural or peri-natural’, but the size of the object in which they inhabit does not relate to their divine power- a Kami at home in a stone could be twice as strong as one that embodies a whole mountain. It is important to note that good and evil as a concept does not fit within the Shinto doctrine, instead Kami are viewed with the idea of Pure versus Impure, with purity referring to anything that hasn't been touched by death. It is thought that all Kami have the capability to commit violent actions, therefore they are worshipped at shrines, where ritual prayers are performed and material offerings are made in an effort to appease the Kami. If properly honoured, the Kami may bless worshippers with guidance and protection. Japanese women have been known to offer their hair to Kami at shrines, and in return the Kami should protect their loved ones during war or hardship- It is evident that the relationship between the Japanese and the Kami is one of give and take.

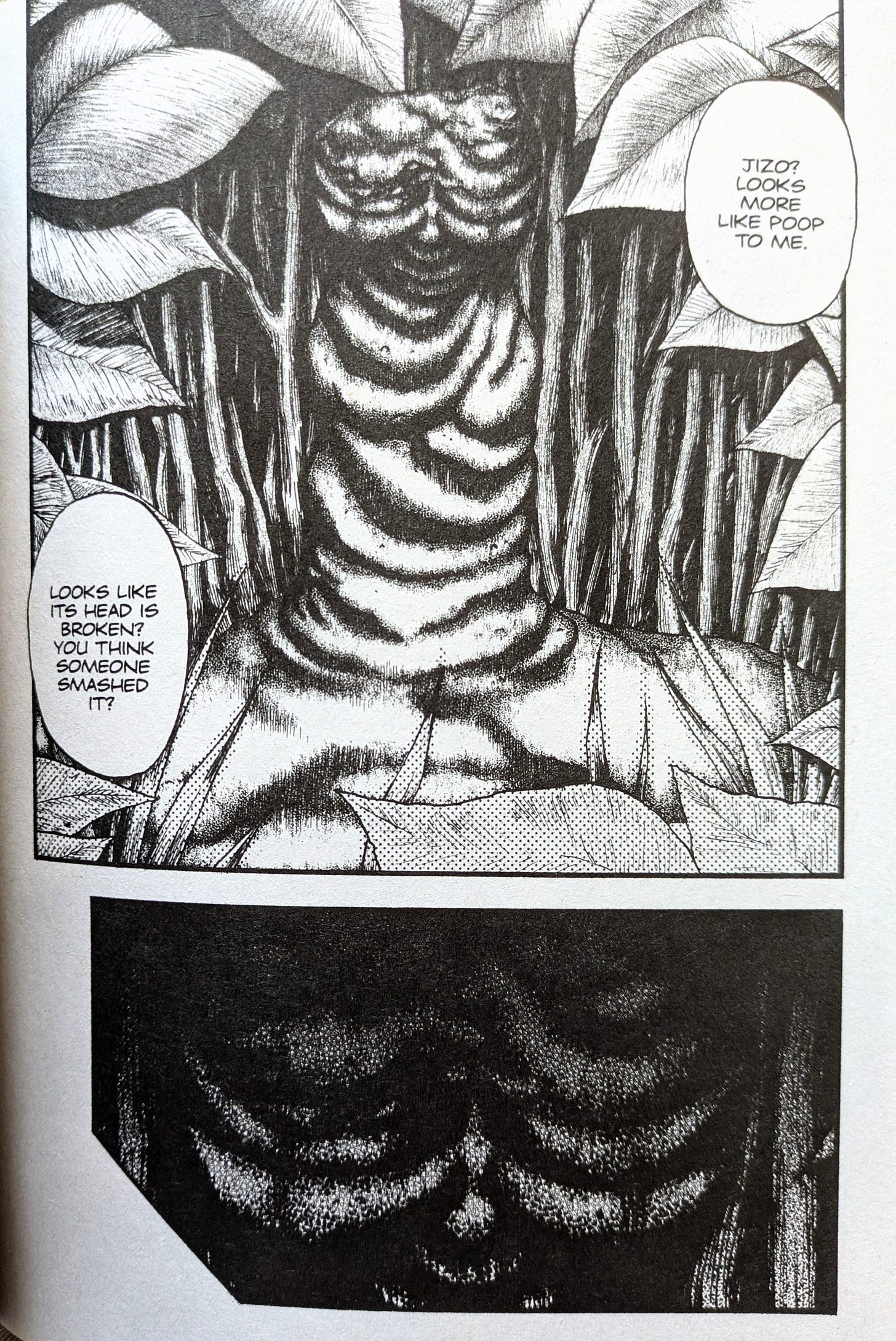

The way that people live amongst the Kami is prevent throughout much of PTSD Radio, portrayed through the worship of ‘Ogushi-Sama’ a Kami residing in a roadside idol. Ogushi-Sama, is a fictional deity but deeply resembles a Jizō statue in both form and function, both statues are visually quite phallic, a representation of a male dominated past and both serve to guide souls to another realm. The Jizō was referenced due to its extreme popularity in Japan, even those who are not religious will pray to the Jizō as they pass one as they are said to protect travellers and guide them to their destination, whether they are dead or alive. With his friendly face, the Jizō is seen as protector of children, especially ‘those who died before their parents’, acting as a proxy father figure.

In chapter 015, Nakayama illustrates a mourning family performing a ritual offering to their village deity, Ogushi-Sama. The young girl's mother has passed, and she is giving the idol a box with the deceased’s shaved hair so that in return the Kami will lead her soul ‘to it's proper resting place’. This flips the Jizō connection around, instead of protecting the child, it is the parent being shielded by the Kami. The shaving of the dead’s hair is contextually important, as it again is referencing the Onryōu. A woman's hair in life can signify wildness, but through death becomes ‘polluted’, giving the woman the potential to become a malevolent presence. This would have been a concern for the deceased in this story, as she died whilst her child was still young therefore not meeting the societal expectations of raising them until adulthood. Therefore by shaving her head, the woman's evil side would be contained and in the same vein as monks, would serve to deny any impurity or materiality, stripping the dead of any social responsibility. By offering the whole set of hair to the Kami, the whole soul of the deceased is being given as well due to the Japanese belief that hair is a physical manifestation of a person's life force. Narratively, this would make Ogushi-Sama extremely powerful, much like the Jizō, as he is in control of the whole sense of the person at their death. Nakayama conveys Ogushi-Sama’s extreme power with his page composition,the idol is looming over the offering, hungry for the energy and pride this will grant him.

Subchapter 2: Modern Japan's Religious Decline/

In other vignettes that play out in a more modern setting, Ogushi-Sama is seen to have fallen into a state of disrepair, looking less phallic, as if he has been emasculated. While Japan hasn't forgotten tradition within their culture, as time passes less of an importance is placed on religion, especially with the younger generation of whom do not want to be aligned with their elders. Nakayama depicts this, with the visage of Ogushi-Sama still standing, yet hidden amongst foliage instead of proudly displayed like in the years lost. The idol’s physical warping is an outward reflection of Ogushi-Sama's emotional state, his fury at his declining presence in the minds of the Japanese people. Nakayama draws in a heavier palette here, showing his own personal distain for Japan's shift into materialism, more reminiscent of western sensibilities.

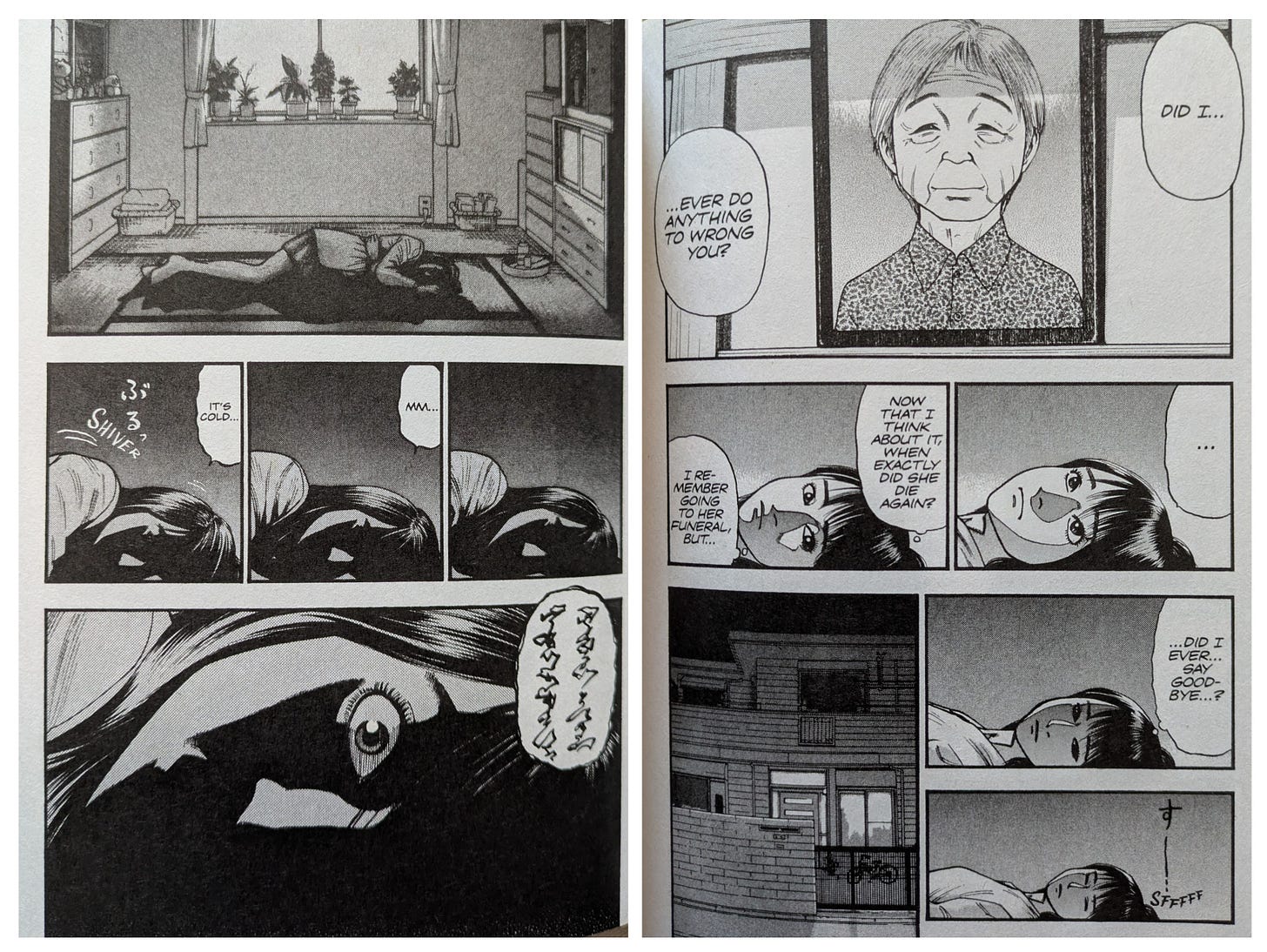

It is for this reason that women are most often being tormented within PTSD Radio, as they have been more open to material culture in general, and are actively rebelling against the old traditions set to oppress them. In chapter 4, a teenage girl is being haunted by her grandmother after not being sent off properly with funeral rites. In the Japanese family, ancestors hold the same spiritual weight as the Kami do, and must be tended to in the same way at shrines with prayer and offerings. Therefore the girl’s inability to perform her duty to her grandmother would have evoked a great feeling of shame amongst both her living and deceased relatives. This emotion in conjunction with the lack of spiritual release gained through funeral rites would leave her grandmother open to be possessed by Kami with vicious intent, through the vehicle of her hair.

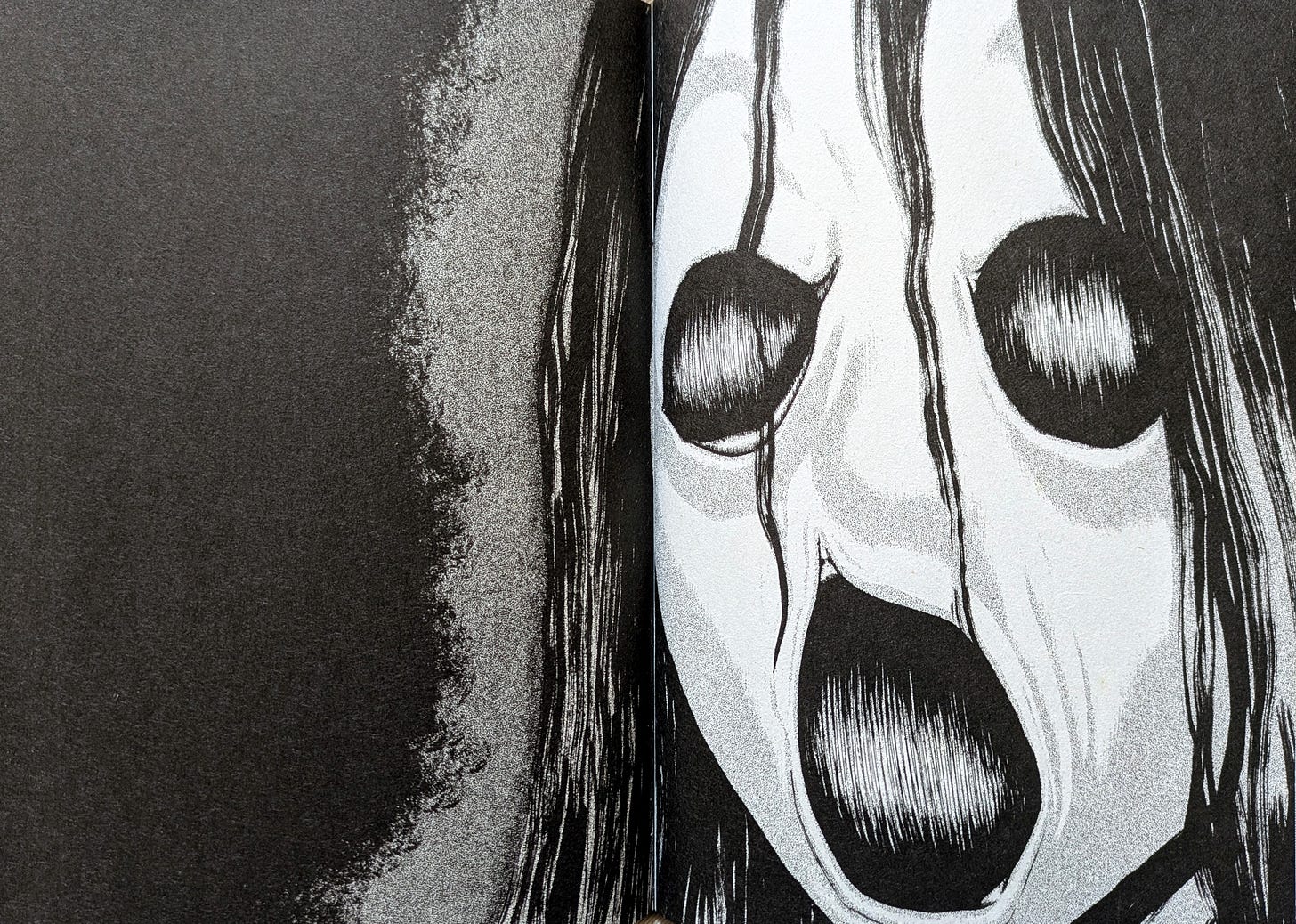

In this case,Ogushi-Sama is using the image of a grandmother for revenge, Nakayama's way of communicating the disrespect that younger generations are inflicting onto their bloodlines. It can be seen that the grandmother Onryōu is more humanoid than the one seen in Chapter 4 (See the first part of this essay), showing that it is not a host to a plethora of unrelated people. Instead the dark hair filling the vaginal eye and mouth holes signify the female ancestors that would have given Ogushi-Sama their symbolic life force in eras long passed. They feel a collective rage alongside Ogushi-Sama at being forgotten, also dealing with pain caused by modern women not conforming to the men's expectations of them. The strands of hair signify familliaral bonds, and the connection to the gods, so the fact that they are being used for malevolence paints Nakayama's viewpoint that Japan has irreversibly severed it's bonds with it's previously respectful past, bringing upon Japan's ruin.

[5] Conclusion

At the heart of Japanese culture, tradition lies, managing to persist even in a modern day due to mediums like manga painting Japan's history in a new light, for a younger audience. Manga was never intended for westerners, therefore has the ability to be ‘Culturally specific and rooted in shared values’, meaning that it is often used to convey political views, as was apparent in PTSD Radio.

Nakayama's clever repetition of the hair motif drew on social and religious references specific to Japan, which once understood adds a dual narrative to the manga. This narrative is purposefully vague as to not alienate it's viewers that do not understand it's context. The overall image painted shows Japan's changing landscape, transforming from a country ‘sealed off by blood and tradition’ to somewhere more westernised, this adoption of materialism destroying Japan's otherness, which is quite reminiscent of the themes in ‘Ringu’.

Nakayama's male lens zooms in on women's role in this change, making connections to the Onryōu, the symbolic entity of a women outcast by society for ignoring her expected duties. His hairy Onryōu are a political device, a warning to not forget tradition in favour of being swept up in a more ‘liberated’ westernised culture. The phallic Kami ‘Ogushi-Sama' inhabits deceased feminine bodies to torment, a symbol of the older generations outrage of the want to leave them behind in the past.

A lot can be learnt from how Nakayama approached the narrative in PTSD Radio, that can be applied in ones own creative practice. The idea of visible versus invisible storytelling is significant as it allows the artist to cater to a wider audience without risk of alienation. But those who understand the source material or cultural contexts that are being referenced will have an enhanced experience. Nakayama condensing research into a singular repeated motif was a clever way of using purely visual storytelling, as it enabled him to add his own personal politics into the story for a more engaged viewer to find, without letting those who want a more casual viewing experience to feel as if they are missing out. Therefore if done in a way similar to Nakayama, cultural politics and mythic histories can elevate graphic narratives without being centre stage.

Resources//

I read a LOT so that I could write on this topic as intelligently as possible. Here are the sources I drew from, please have a look if you are interested in reading further into Japanese Horror:

Images:

Nakayama, M. (2012) All from ‘PTSD Radio Volume 1’

Nakata, H. ‘Ringu’ [See Part 1]

Websites:

Loveridge, L . (2023) For ‘The Anime News Network'. ‘The Quiet Terror of PTSD Radio with Eisner -nominated Horror manga creator Masaaki Nakayama' Available at:

Exhibition (Primary Research):

Young V&A, London (2024) ‘Japan: From Myths to Manga’

Books:

Ashkenazi, M. (2008) ‘Handbook of Japanese Mythology’

Published by Oxford University Press

Balmain, C. (2008) ‘Introduction to Japanese Horror Film’

Published by Edinburgh University Press

Batchelor, J. (2020) ‘The Ainu of Japan: The religion, superstitions and general history of the hairy aborigines of Japan'

Published by Alpha Editions

Booth, R. (2020) ‘Scared Sacred: Idolatry, Religion and Worship in the Horror Film’

Published by House of Leaves

Cherry, B. (2009) ‘Routledge Film Guidebooks: Horror's

Published by Routledge

Foster, M.D. (2015) ‘The Book of Yokai: Mysterious Creatures of Japanese Folklore’

Published by University of California Press

Frydman, J. (2022) ‘The Japanese Myths: A Guide to God's, Heroes and Spirits’

Published by Thames and Hudson

Gravett, P. (2004) ‘Manga: Sixty Years of Japanese Comics’

Published by Laurence King Publishing

Irvine, G. (2016) ‘Japanese Art and Design’

Published by V&A Publishing

Kinsella, S. (2000) ‘Adult Manga: Culture and Power in Contempory Japanese Society'

Published by Curzon Press

Littleton, C.S. (2002) ‘Understanding Shinto’

Published by Duncan Baird Publishers

McCloud, S. (1993) ‘Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art’

Published by Harper Collins

McRoy, J. (2005) ‘Japanese Horror Cinema’

Published by Edinburgh University Press

McRoy, J. (2008) ‘Nightmare Japan: Contempory Japanese Horror Cinema'

Published by Rodopi

Miller, B.D. (1998) ‘Hair: It's power and meaning in Asian Cultures’

Published by State University of New York Press

Minear, R.H. (2008) ‘Through Japanese Eyes’

Published by Rowman and Littlefield

Nakayama, M. (2023) ‘PTSD Radio' Volume 1-3 Omnibus, Western release’

Published by Kodansha

Noble, I. & Bestley, R. (2016) ‘Visual Research: An introduction to Research methods in Graphic Design’

Published by Bloomsbury

Norbury, P. (2021) ‘Japan: The Essential Guide to customs and culture’

Published by Kuperard

Summerscale, S. (2022) ‘The Book of Phobias and Manias: A history of the world in 99 Obsessions'

Published by Profile Books

Suzuki, K. (1991) ‘Ring’

Published by Kadokawa Shoten

Tipton, E.K. (2016) ‘Modern Japan: A social and political history (Third Ed)’

Published by Routledge

Wiedemann, J. (2021) ‘100 Manga

Artists' Published by Taschen GmbH

Thank you for reading! Let me know what you thought! If you haven't read part 1, please do so- there is way more context there.